Image of the old (7 Gyr) open cluster NGC 188 taken at the WIYN 0.9m telescope; blue stragglers are circled.

Credit: K. Garmany, F. Haase NOAO/AURA

Research

Gravitational dynamics has stood as a foundation of astronomy since Sir Isaac Newton modified Kepler's third law to show that the motions of our planets can be described by orbits around a central force of gravity. Motion due to the effects of gravity is perhaps one of most relatable areas of physics, as we experience the influence of gravity on a daily basis. Stellar systems like open and globular star clusters offer a particularly rich dynamical environment, where two-body relaxation drives a relatively rapid evolution and close encounters between individual stars and binaries can occur on a regular basis.

Here you will find descriptions of a number of exciting research projects that my collaborators and I are pursuing to study the effects of stellar encounters on the evolution of multiple-star systems, planetary systems and star clusters.

Please note that I am not accepting new students at this time.

Quick Links to Projects

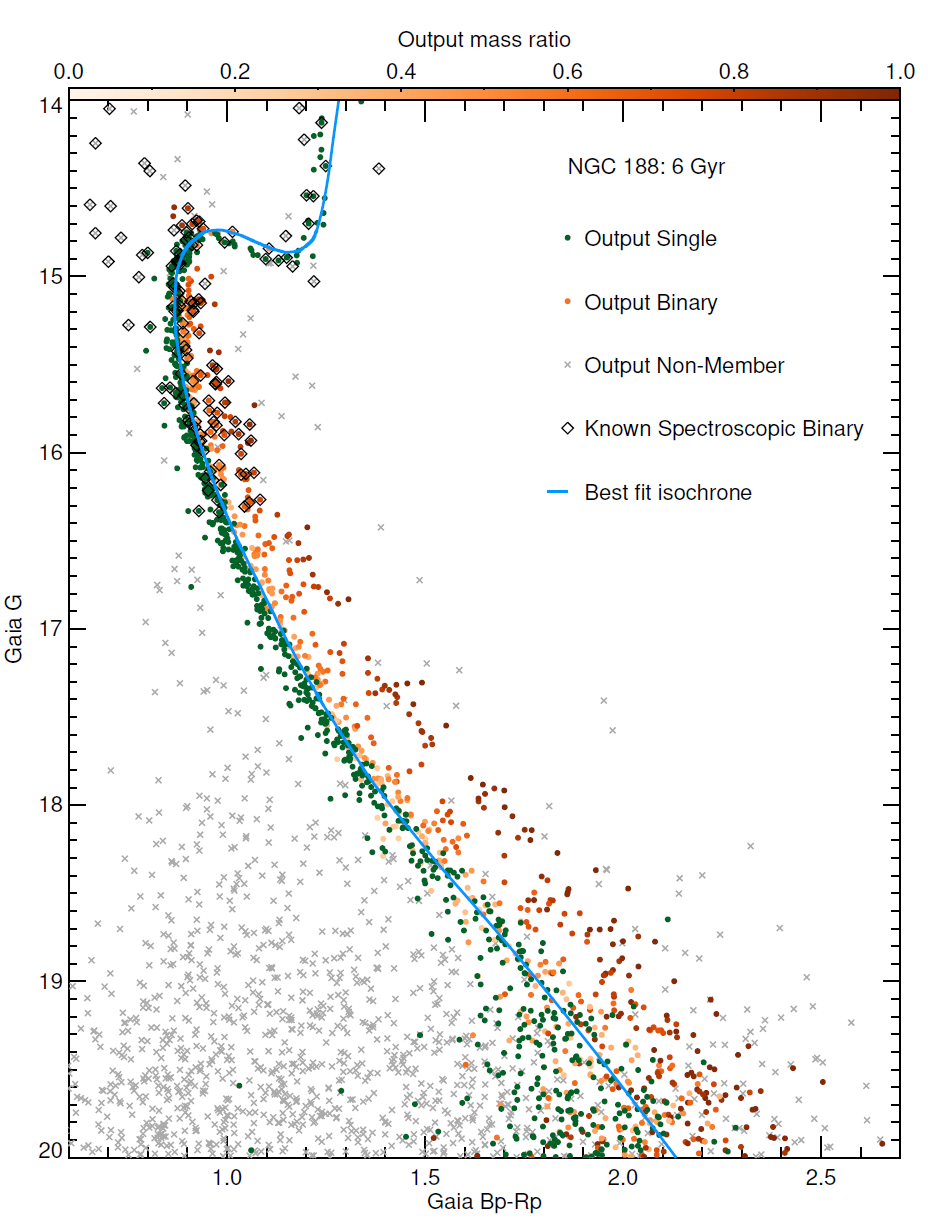

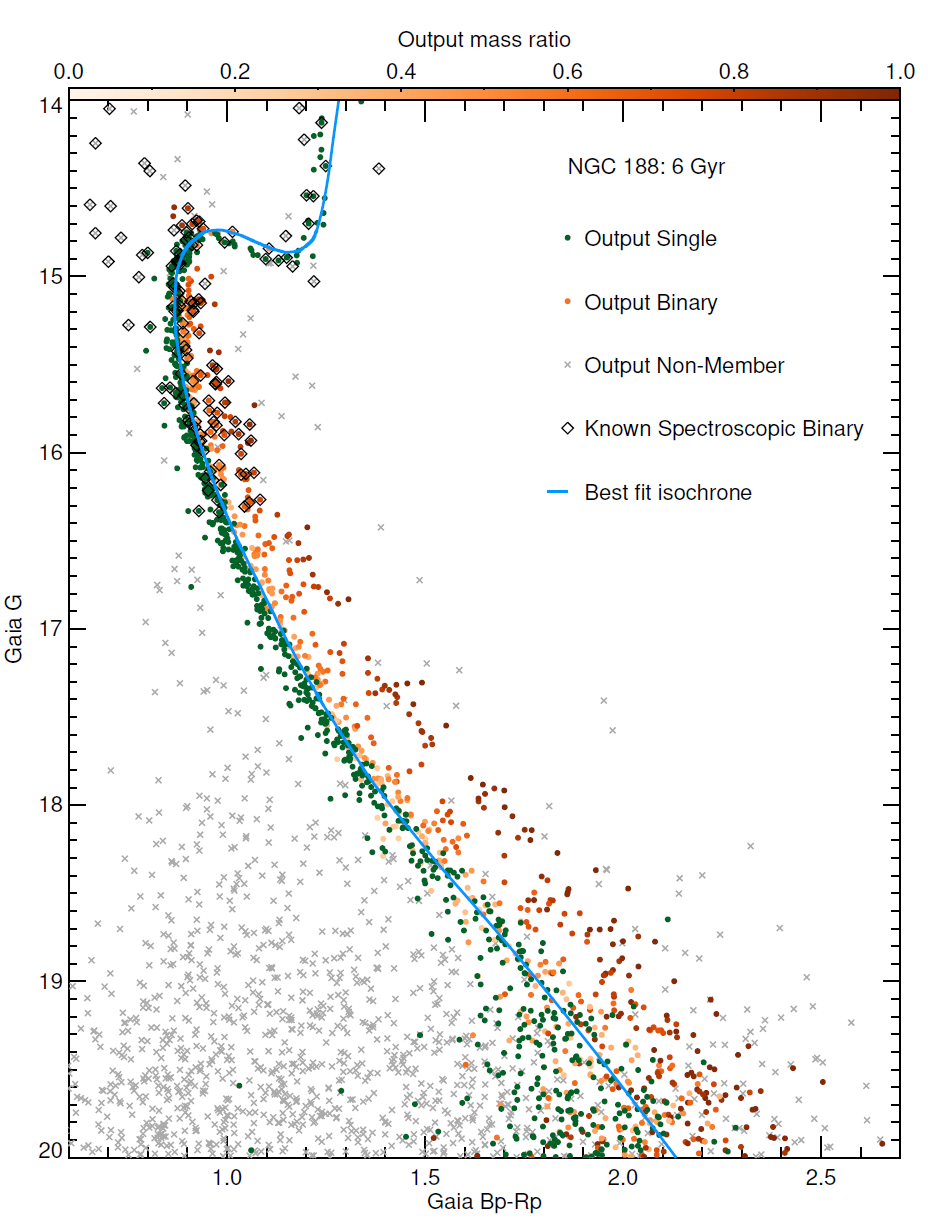

Photometric Binary Stars

Color-magnitude diagram showing results from a Bayesian model fit using BASE-9 to the old open cluster NGC 188. Photometric binaries identified by BASE-9 are highlighted.

Credit: Roger Cohen

Observations of stars in our Galaxy show that about 2/3 of the stars like our Sun reside in close pairs, called "binary stars". Furthermore, many of these stars are born within larger families known as "star clusters". Observations of such stars provide a foundation for the theories of stellar formation and evolution. In turn, these theories underpin much of stellar astrophysics. Yet despite how common and important binary stars are, vital questions remain unanswered. My collaborators and I are investigating two such questions specifically:

- How does the local environment affect the birth characteristics of binary stars?

- How are these birth characteristics modified over time by the star cluster environment?

To answer these questions, we will self-consistently characterize the binary star populations in hundreds of open star clusters, across a wide range of cluster properties, using the state-of-the-art Bayesian Analysis of Stellar Evolution (BASE-9) tool. For each cluster, we will compile available photometry from Gaia, 2MASS and Pan-STARRS, and use these data within the BASE-9 software to

- identify photometric binaries and determine their masses and mass ratios,

- establish the cluster age, distance, reddening and metallicity, and

- derive star-by-star photometric membership probabilities and masses.

We will use this database to examine predicted trends in binary frequency and mass-ratio distribution

- across different clusters (as functions of, e.g., age, metallicity, density, cluster mass, etc.) as predicted by stellar dynamical and star formation models, and

- within each individual cluster (e.g., as a function of distance from the cluster center) as predicted by two-body relaxation and mass segregation effects.

This analysis will produce a large database of the empirical properties of binary stars and their host star clusters, which we will make availabled to the community through a custom-built online interactive table and plotting utility. This database will help enable follow-up stellar astrophysics studies, including spectroscopic binary observations, stellar oscillations research, and tests of gyrochronology and stellar evolution models.

Collaborators: Anna Childs, Roger Cohen, Ted von Hippel, Elizabeth Jeffery

Homepage: For more information about the project, including publications, and an interactive online tool to explore our database of photometric binary stars in open clusters, please visit our Open Cluster Binary Explorer website.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. AST-2107738. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Back to top

WIYN Open Cluster Study (WOCS)

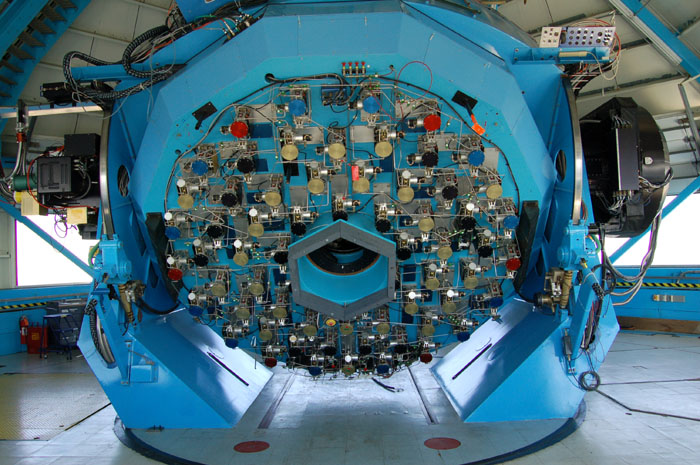

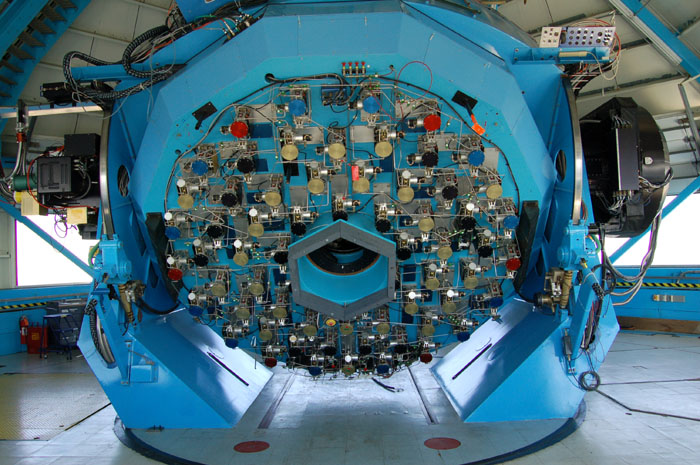

Photograph of the back of the WIYN 3.5m telescope, showing the mirror actuators which push or pull on the back face of the mirror to maintain the best optical figure. The WIYN telescope is located on Kitt Peak near Tucson, Arizona.

Credit: A. M. Geller

The WIYN Open Cluster Study (WOCS). is a collaboration spanning more than a decade with members at over a dozen universities. The goals of WOCS are to obtain precise and comprehensive photometry, spectroscopy and astrometry for stars in open clusters spanning a wide range in age and metallicity. My primary contributions to WOCS have been stellar radial-velocities for thousands of stars in the open clusters:

Through our observations, we are defining the cluster member population and analyzing the spectroscopic binaries (binary fraction, frequency distributions of orbital parameters, mass ratios) for binaries with orbital periods approaching the hard-soft boundary. These observations also provide a comprehensive survey for anomalous stars, including secure establishment of their cluster membership. Importantly, these observed binary population provide essential guidance for sophisticated N-body open cluster simulations, from which we are studying how stellar encounters modify a population of binary and multiple-star systems and planetary systems, and influence the evolution of star clusters.

Recently we have added a few new open clusters to the survey, including two in the Southern Hemisphere:

These clusters (as well as M35) are all young, and therefore they provide important information about the near-primordial stellar populations in open clusters. Furthermore, these four clusters fill an important niche as a bridge between the Pleiades (100 Myr) and the Hyades (750 Myr), and will be used to relate both of these young and well-studied clusters and to search for evolutionary signatures. My personal interest lies in defining the binary populations in these clusters, specifically binary frequency and distributions of orbital parameters (e.g., period, eccentricity, mass ratio). These near-primordial binary populations provide essential, and hitherto unknown, guidance for defining the initial stellar populations in numerical N-body models.

Collaborators: UW WOCS group, full WOCS team

Papers: Geller et al. (2008, 2009, 2010, 2011), Hole, et al. (2009), Gosnell, et al. (2011)

Back to top

Cluster Membership

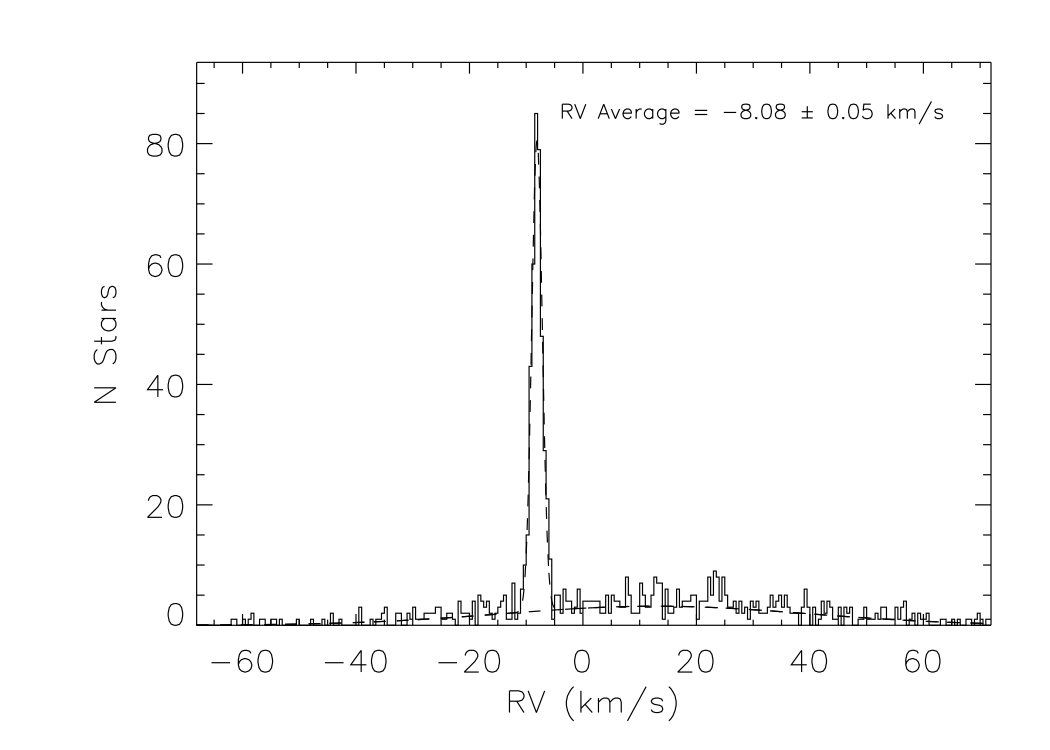

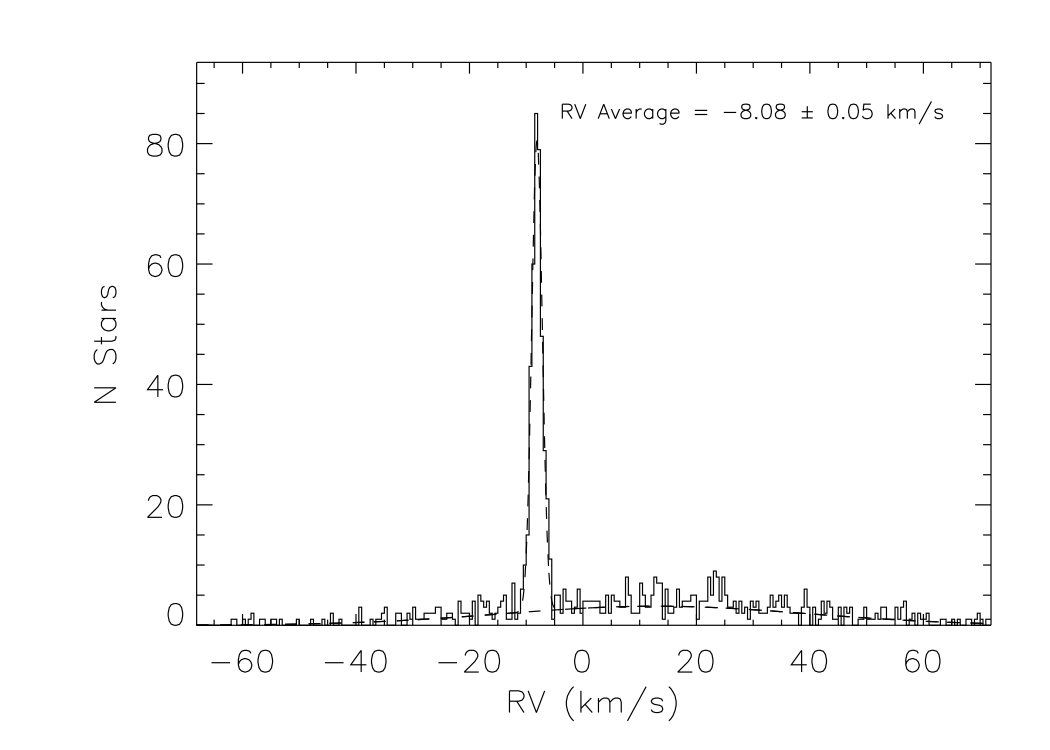

Radial-velocity (RV) histogram for stars in the field of M35. Cluster members are clearly identified by the sharp peak in the distribution at the mean RV of about -8 km/s. Stars in the Glactic field, not associated with the cluster, have a significantly broader RV distribution. The dashed lines show the simultaneous Gaussian fits to the cluster and field RV distributions. We use these Gaussian fits to calculate membership probabilites for each individual star in the cluster.

Credit: A M. Geller, et al. (2010, AJ)Determining cluster membership is the fundamental first step to studying any star cluster. All members of a star cluster move with a very similar velocity (to within the cluster velocity dispersion, which is typically <1 km/s in open clusters), while field stars have a much wider range in velocities. Therefore analyzing the observed stellar radial-velocities (the primary product of our spectroscopic surveys) separates stars that are members of the cluster from interloping field stars that are actually in front of or behind the cluster. This analysis is particularly important, as many open clusters are found in or near the disk of our Galaxy, amidst a rich population of Galactic field stars.

I have personally determined radial-velocity membership probabilities for thousands of stars in the open clusters NGC 188, M35 and NGC 6819, and I am currently working on performing a similar analysis for stars in M67. We are poised to begin our membership analyses of M37, NGC 3532 and NGC 2516, which would be ideal short-term student projects. I am also involved in determining the cluster members of NGC 7789 and NGC 2516; these projects are led by graduate students at the University of Wisconsin - Madison.

Once cluster members are determined, we can explore a wide range of exciting projects, including studying the binary population (e.g., determining the binary frequency and distributions of orbital parameters) or identifying exotic stars like blue stragglers. We can even use these observations to guide sophisticated numerical simulations to study the past and future evolution of the cluster.

Collaborators: Bob Mathieu, Natalie Gosnell, Katelyn Milliman, Søren Meibom, David Latham, Sydney Barnes, David James, Hugh Harris

Papers: Geller et al. (2008, 2010), Hole, et al. (2009)

Back to top

Kinematic Binaries and Multiple-Star Systems

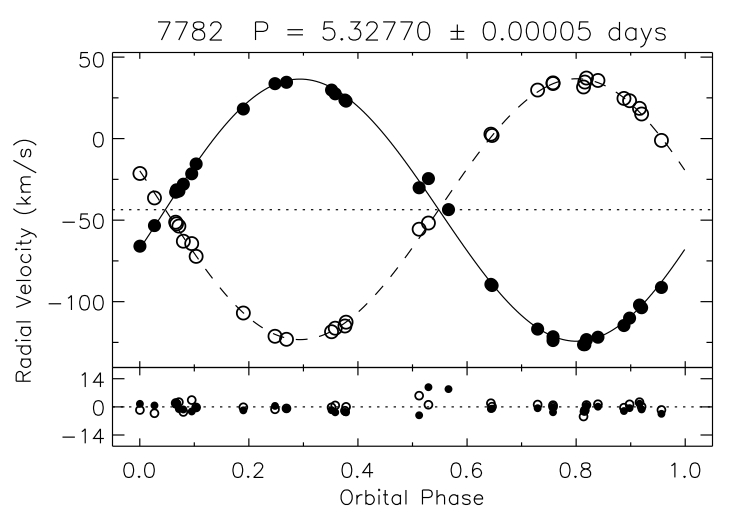

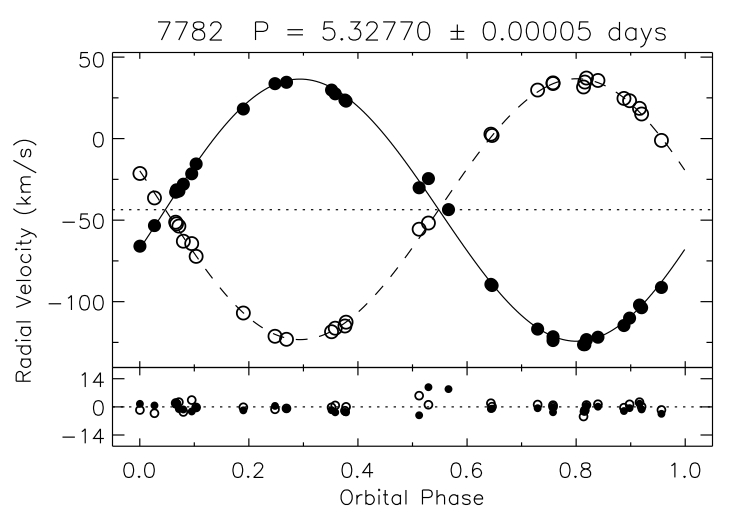

Radial-velocity (RV) as a function of orbital phase for the blue straggler binary ID 7782 in NGC 188. This particular binary is "double lined" meaning that we detect the flux from both stars in our spectra. The primary RVs are shown in the solid points, and the secondary RVs are shown in the open circles. The lines show the kinematic orbital solution. In the bottom panel, we show the RV residuals (observed - expected) .

Credit: A M. Geller, et al. (2009, AJ)A binary companion star will pull on its partner as they both orbit about their mutual center of mass. This pull is detectable within a time series of radial velocities for a given star by examining the radial velocity standard deviation or through a chi-squared analysis. Given a long enough time baseline of observations for a binary, we can solve for the orbital solution to determine the period, eccentricity, mass ratio, etc. , which are particularly important for characterizing eclipsing binaries (like those that will be discovered by LSST) and for guiding sophisticated N-body open cluster simulations.

I have studied the binary population in the old open cluster NGC 188 in detail. In Geller et al. (2009) we present the kinematic orbits for 98 binaries within the field of NGC 188 (the orbit for blue straggler binary 7782 is shown in the Figure on the right). We are currently working on completing our analysis paper in which we determine the binary frequency and distributions of orbital parameters for the main sequence, giant and blue straggler cluster members. I am also leading the analysis of the binaries in M67 and M35, and working with my WOCS colleagues at the University of Wisconsin - Madison to examine the binaries in NGC 6819, NGC 7789 and NGC 2516.

In our NGC 188 binary analysis paper, we also compare the NGC 188 binaries to those from a recent N-body open cluster model (created by my collaborator Jarrod Hurley). We find that the standard assumptions used to define the initial binaries in such models result in mature binary populations that are significantly different than real binaries in true clusters like NGC 188. This finding motivated us to create a more realistic open cluster model, as discussed below, by defining the initial binaries directly from observations of young open clusters.

Indeed binary populations used in numerical simulations have long been based upon theoretical inferences and predictions. Yet the binary population dictates the dynamical evolution of the parent open cluster. Furthermore, the details of dynamical encounters are determined in a large part by the orbital parameters and masses of the binaries involved. Therefore accurately modeling the effects of dynamical encounters on stellar (and planetary) systems in star clusters requires an accurate initial binary population. A robust empirical definition of the initial stellar population can only be achieved through the study of young open clusters (ages <500 Myr), such as M35, M37, NGC 3532 and NGC 2516.

Collaborators: Bob Mathieu, Natalie Gosnell, Katelyn Milliman, Søren Meibom, David Latham, Sydney Barnes, David James, Keivan Stassun, Hugh Harris

Papers: Geller et al. (2009, 2011), Stassun et al.(2008)

Press: For Stassun et al. (2008):

Back to top

Exotic Stars

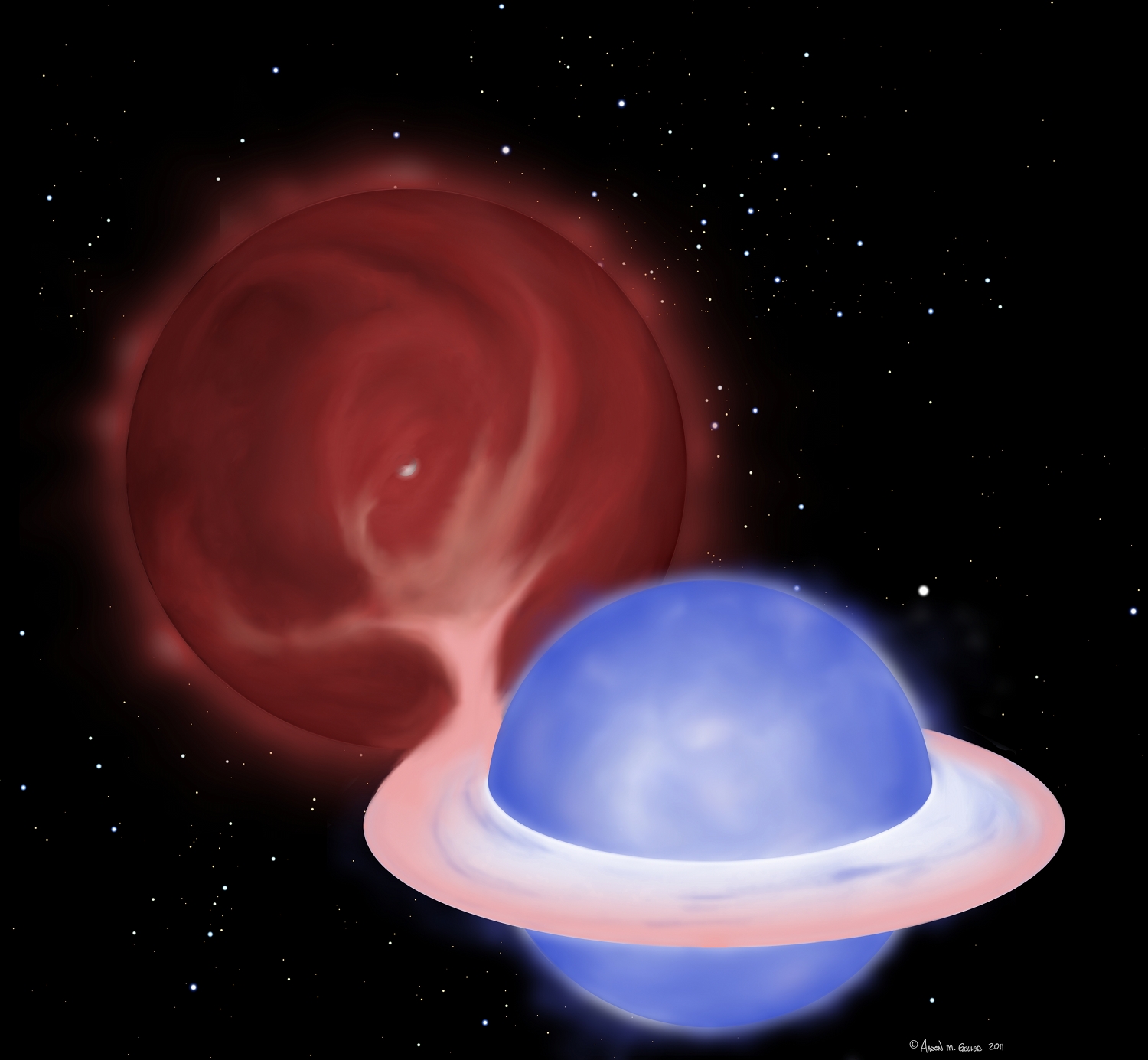

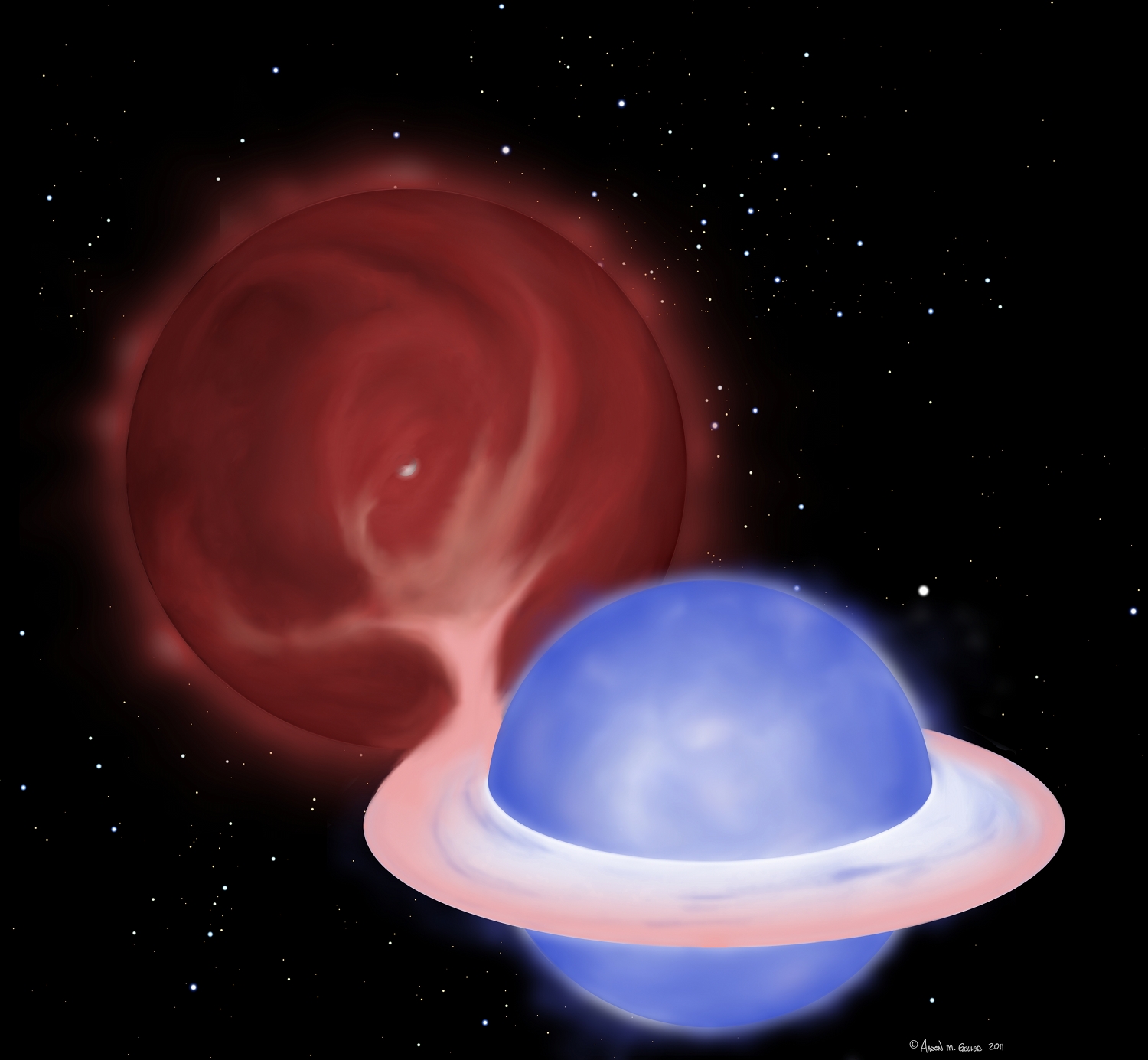

My artistic representation of a blue straggler being created by mass transfer in a binary star system. The giant star, seen in the upper left of the illustration, has lost hold of its outer envelope. This material is pulled towards its partner, forming an accretion disk, and is eventually consumed by the "proto-blue straggler", seen in the lower right of the illustration. Soon the giant star will donate the remainder of its envelope, leaving only the half-solar-mass white dwarf core (shown peaking through the giant's tenuous envelope) as the companion to the blue straggler.

Credit: A. M. Geller

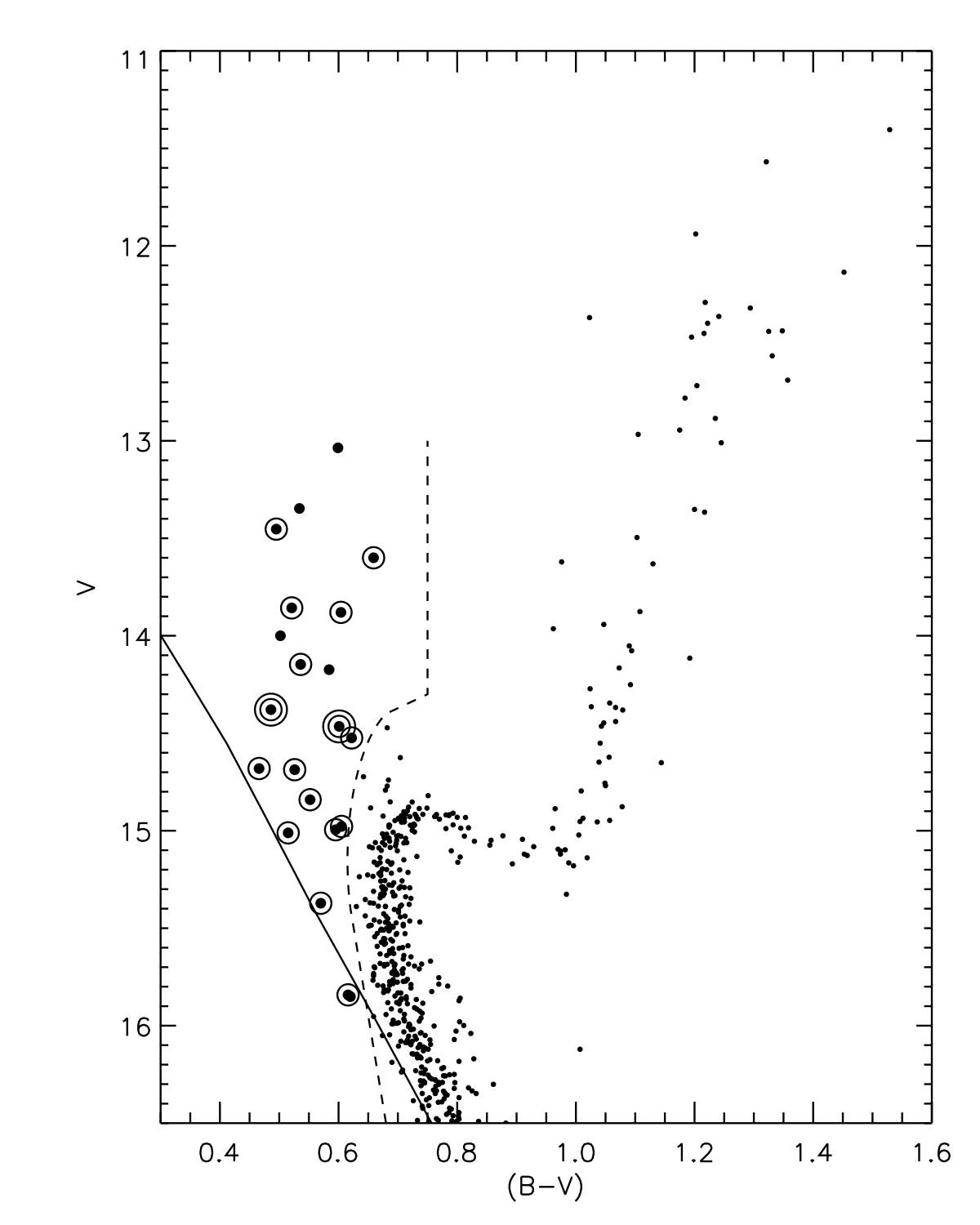

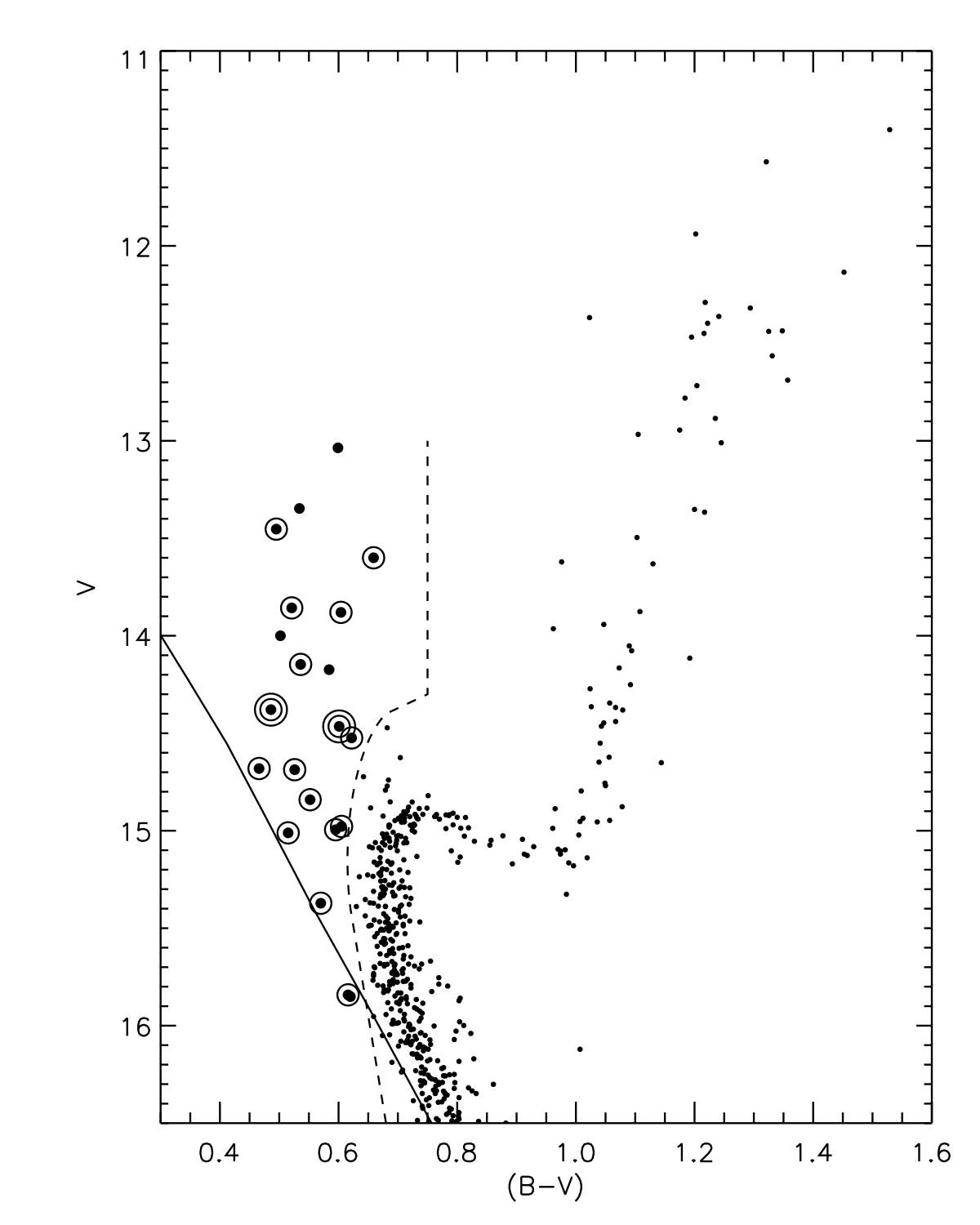

Brightness (increasing upwards) in V magnitudes versus color (redder and cooler to the right) in

B-V magnitudes. The 21 blue stragglers are shown as larger black dots, with the 16 binaries circled (and the two double-lined binaries marked with 2 concentric circles), and are identified as being to the left of the dashed line at a given brightness. The line is drawn so as to not include binaries comprising two normal stars from the cluster turn-off region, which consequently are brighter in combination. For reference, we also show a zero-age main sequence (solid line). Normal single stars spend most of their main-sequence lives very near this line until their core hydrogen supply is exhausted and they evolve towards the giant branch.

Credit: R. D. Mathieu & A. M. Geller (2009, Nature)

Recently, through careful cluster membership analyses, we have found rich populations of exotic stars. These stars are not predicted by stellar evolution theory and instead derive from stellar collisions, mergers, mass transfer and dynamical encounters, many of which are facilitated by binary stars. The "blue stragglers" are the most well studied example, and are generally identified by their unique location on the color-magnitude diagram, being hotter and brighter than the main sequence turnoff stars. Other exotic stars can be identified by rapid rotation (which is easily detected in our spectroscopic data), X-ray emission (e.g., in our XMM-Newton observations), and also through unlikely binary orbits.

Lately, I have been particularly interested in blue stragglers. Blue stragglers are stars observed to be brighter and bluer than normal main sequence stars of a similar mass and age, and therefore long ago should have evolved to become giant stars and stellar remnants. Since the discovery of blue stragglers, some 60 years ago in the globular cluster M3 by Allan Sandage, blue stragglers have been observed in essentially every stellar population where astronomers have looked, from the very dense cores of globular clusters, to the moderately dense open star clusters, to the sparse regions of the Galactic field. Astronomers have been debating the origins of blue stragglers within these various environments since their discovery. The currently accepted theories include formation through collisions, mergers and mass transfer.

Stellar collisions can occur in the dense regions of star clusters when two stars physically run into each other, and combine to form one more massive star, that would then be observed as a blue straggler. It is most likely that such collisions would occur as a result of dynamical encounters involving binary stars, given their larger physical cross sections for interactions. Therefore a blue straggler created in a collision may retain a companion that participated in the encounter.

Mergers are similar to collisions in that two stars come together to form one blue straggler. However in this scenario the stars begin bound in a close binary system. In fact, the two stars are so close that, given an angular momentum loss mechanism (like magnetic braking), the two stars eventually touch and spiral in to merge. This particular scenario would produce a single blue straggler. Recently this mechanism has been discussed in the context of a triple star system where Kozai cycles drive the inner binary to high eccentricity, and tidal dissipation during close pericenter passages shrinks the orbit to induce a merger. In this new scenario, the original tertiary star would remain bound to the blue straggler as a binary companion.

Mass transfer also occurs within a binary system, but in this scenario the stars do not merge. Instead one star evolves to become a giant and then overfills its Roche Lobe. The giant transfers mass from its envelope to the main sequence star, which accretes the material and eventually becomes a blue straggler. Once the giant has donated its entire envelope, all that remains as a companion to the blue straggler is a white dwarf (the remnant core of the giant star donor), which is predicted to be about 0.5 solar masses. This scenario is shown in my illustration to the right.

Along with my collaborator Bob Mathieu from the University of Wisconsin - Madison, I tested these formation hypotheses against our observations of the blue stragglers in the old (7 Gyr) open cluster NGC 188. The NGC 188 blue stragglers have a remarkably high binary frequency, and nearly all of the companions to the blue stragglers orbit with periods near 1000 days. Importantly, we also find that these long-period blue straggler binaries in NGC 188 all have companions of about half a solar mass.

Through comparisons of these detailed observations to blue stragglers created within our sophisticated N-body model of NGC 188, we conclusively rule out an origin in collisions for these long-period blue straggler binaries. Blue stragglers formed by collisions, which remain in binaries, have significantly higher-mass companions and significantly higher eccentricities than are observed. Mergers in hierarchical triples are marginally permitted by the observations, but the data do not favor this hypothesis. Instead the data are closely consistent with a mass transfer origin for the long-period blue straggler binaries in NGC 188, in which the companions would be half-solar-mass white dwarfs.

This is the first time that the origins of nearly every blue straggler in a star cluster have been determined, and the mass transfer mechanism has emerged as a compelling candidate. We aim to confirm this result through forthcoming Hubble Space Telescope observations which can directly detect the ultraviolet flux from the white dwarf companions predicted by the mass transfer mechanism.

Collaborators: Bob Mathieu, Natalie Gosnell, Katelyn Milliman, David Latham, Nathan Leigh, Alison Sills

Papers:Geller & Mathieu (2011), Mathieu & Geller (2009), Gosnell, et al. (2011)

Press: For Geller & Mathieu (2011):

For Mathieu & Geller (

2009):

Back to top

N-body Open Cluster Simulations

Visualization showing a snapshot in time from an

N-body open cluster simulation. The simulation was created using the nbody6 code, and this image was created using my personal visualization software.

Credit: A. M. Geller

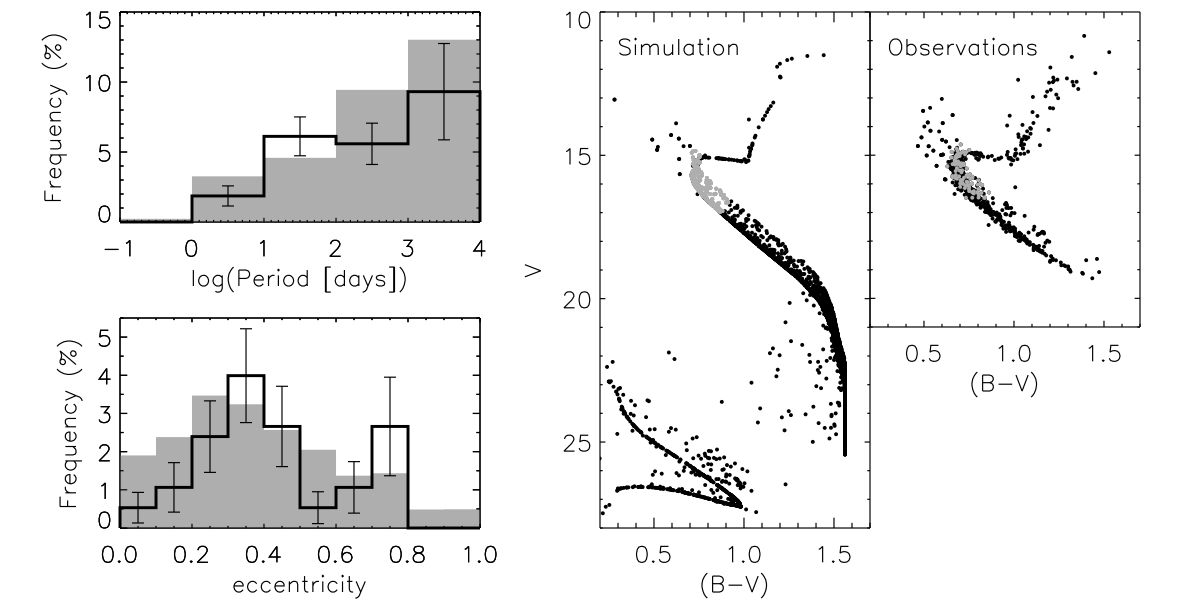

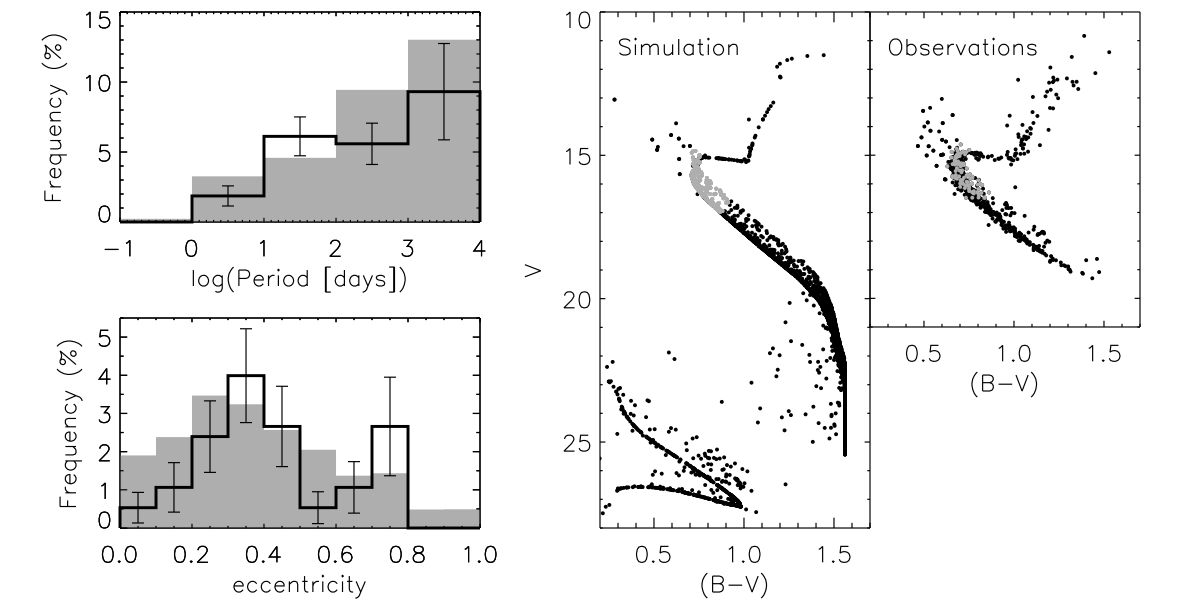

Comparison of the NGC 188

N-body model to our observations. The left panels compare the observed (black line) and simulated (gray-filled) main sequence period (top) and eccentricity (bottom) distributions. The right panel compares the simulated (left) and observed (right) color-magnitude diagrams (with the main-sequence binaries used for the left panels marked in gray). The initial binaries for the NGC 188 simulation were based directly on our observations of the binary population in the young (150 Myr) open cluster M35. The simulation was constructed using the nbody6 code. The remarkable agreement between the binary population in the model and that of the true cluster in both frequency and distributions of orbital parameters demonstrates the power of using detailed observations to guide sophisticated

N-body simulations.

Credit: A. M. Geller

N-body codes have matured over nearly the past half a decade under careful development by Dr. Sverre Aarseth and collaborators, and now the interaction between stellar evolution and dynamics can be modeled self-consistently (e.g. nbody6). The groundbreaking Hurley et al. (2005) open cluster model (discussed briefly above) is a clear example of the potential for such numerical studies to address long-standing questions about binary evolution and the origins of blue stragglers in a specific open cluster. However upon a more detailed comparison of this model to our data, it became clear that critical discrepancies remained, especially in the binary population.

During the 2009 summer, I was awarded an NSF EAPSI fellowship to work with Dr. Jarrod Hurley at the Swinburne Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing to create an accurate N-body model of the old (7 Gyr) open cluster NGC 188. Our innovation was to use our observations of the binary population in the young (150 Myr) open cluster M35 to directly establish the initial binary population in the simulation, thereby replacing the theoretical distributions that have long been used in the absence of detailed observations. The NGC 188 model is the first simulation whose primordial binaries are directly defined by such detailed observations of a young open cluster.

There is no a priori reason to assume that M35 and NGC 188 are on the same evolutionary sequence. Still, at 7 Gyr the simulation matches the observed main sequence binary period and eccentricity distributions and binary frequency with remarkable accuracy, a vast improvement over previous N-body models. The excellent agreement between our model and our detailed observations of the true cluster demonstrates the power of using observations of real binary populations to directly define the initial conditions of open cluster N-body models. Furthermore, the accuracy with which we reproduce the normal binaries in the cluster allowed us to finally investigate the origins of the NGC 188 blue stragglers within a realistic and comprehensive theoretical framework (discussed above).

Collaborators: Jarrod Hurley, Bob Mathieu

Papers: Geller et al. (2008), Geller, Hurley & Mathieu (2009), Geller & Mathieu (2011), and "A Direct N-body Model of the Old Open Cluster NGC 188, Geller, Hurley & Mathieu in prep

Press: For Geller & Mathieu (2011):

Back to top

Exoplanets in Star Clusters

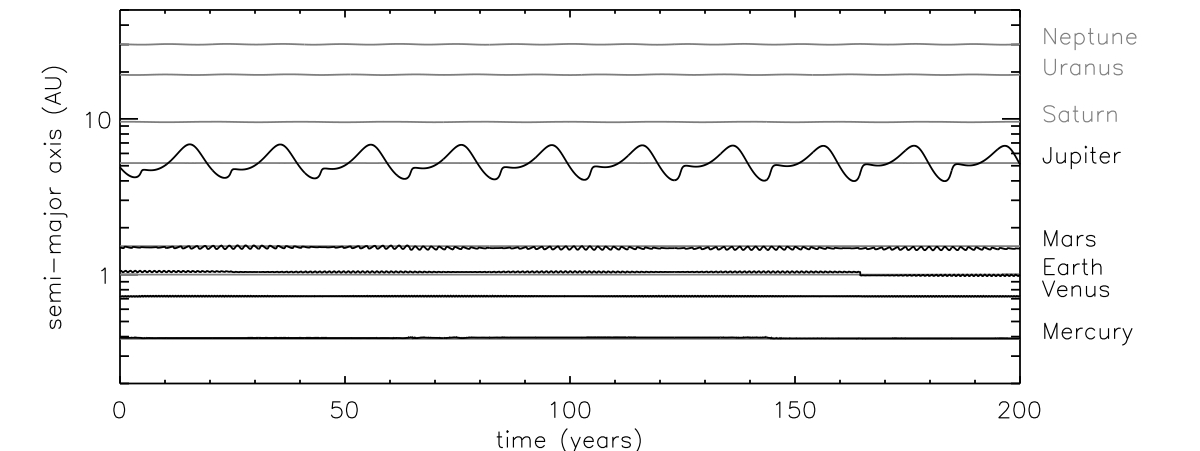

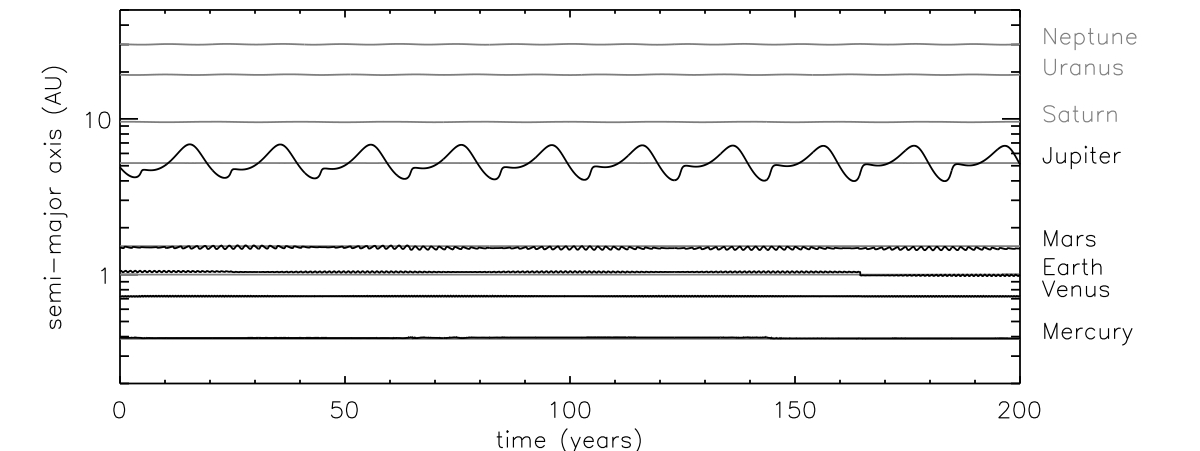

Semi-major axes as functions of time for the planets in our Solar System, produced using the Mercury planetary system integrator. The gray lines show the normal unperturbed system, and the black lines show what our Solar System would look like in the 200 years following a weak dynamical encounter with another star, for instance within an open star cluster. Neptune, Uranus and Saturn are ejected from the system. The rest of the planets survive, but their semi-major axes (as well as eccentricities, and inclinations) are modified, with Jupiter's orbit changed most significantly. I will use as similar method to model the dynamical evolution, including the effects of stellar encounters, of planetary systems within star clusters.

Credit: A. M. GellerA large fraction of stars form in star clusters or cluster-like environments. Indeed many stars found in the field today were likely born in denser environments, and were therefore subject to dynamical encounters with other stars in the past. Such dynamical interactions can reshape a population of planetary systems by modifying their orbits and can potentially lead to their disruption. Furthermore even small perturbations to multiple-planet systems (e.g. those inducing modest changes in eccentricity or inclination) can have catastrophic effects on the system's internal evolution, possibly leading to collisions, ejected planets or the complete disruption of the system. It is therefore remarkable that 34% of observed stars in the Kepler field host at least one planet (a < 0.5 AU), and a third of the planetary systems contain multiple planets.

Though observational surveys of open clusters are not yet ready to answer the question of how the dynamical environment of a star cluster can effect planetary systems (due to small samples and selection biases), N-body simulations can do so today. Furthermore, we can now use our observations of the stellar populations in open clusters, to guide sophisticated star cluster models with greater accuracy than was previously possible.

Soon, I will create an array of N-body open cluster simulation spanning the observed masses and densities for open cluster in our Galaxy, to study how stellar encounters within star clusters effect the dynamical evolution of planetary systems (including those similar to our Solar System). Within these simulations we will track the evolution of planetary systems containing multiple planets to answer the following fundamental questions:

- What fraction of planetary systems can survive in open cluster environments of different masses,densities and ages, and what are their orbital parameters?

- What fraction of the surviving planets are in the habitable regions around their host stars?

- How are the orbital parameters of surviving planetary systems modified by dynamical encounters, and does this vary significantly for different mass host stars?

- What insights do our simulations provide for results from recent observational exoplanet searches in open clusters, and what predictions do our simulations make for future surveys?

- What are the characteristics of planetary systems that escape from clusters, and do they show detectable signatures of dynamical encounters?

Collaborators: Joe Glaser, Steve McMillan, Simon Portegies Zwart, Inti Pelupessy, Jarrod Hurley, Fred Rasio, Yoram Lithwick, Daniel Fabrycky

Back to top

Three-Body Evolution

My collaborators and I are developing the first code that models both the secular dynamics and stellar evolutionary processes of three-body systems. Triple stars have been employed to explain the production of a number of exotic star systems, including certain X-ray binaries, blue stragglers, contact binaries and type Ia supernovae progenitors. With our, we will test these hypotheses in full detail. Dynamical interactions in two-planet systems have been postulated to explain observed retrograde planets and "hot Jupiters". We will use our code to explore the effects of stellar evolutionary process on these mechanisms. Additionally, we will study the stability of a planet orbiting an evolving binary star, which is particularly exciting given the first circumbinary planet recently discovered by Kepler.

We are currently in the development stages of this code, and expect to have the code completed by early 2012.

Collaborators: Smadar Naoz, Hagai Perets, Paul Kiel

Back to top

Image of the old (7 Gyr) open cluster NGC 188 taken at the WIYN 0.9m telescope; blue stragglers are circled.

Image of the old (7 Gyr) open cluster NGC 188 taken at the WIYN 0.9m telescope; blue stragglers are circled.  Color-magnitude diagram showing results from a Bayesian model fit using BASE-9 to the old open cluster NGC 188. Photometric binaries identified by BASE-9 are highlighted.

Color-magnitude diagram showing results from a Bayesian model fit using BASE-9 to the old open cluster NGC 188. Photometric binaries identified by BASE-9 are highlighted.

Radial-velocity (RV) histogram for stars in the field of M35. Cluster members are clearly identified by the sharp peak in the distribution at the mean RV of about -8 km/s. Stars in the Glactic field, not associated with the cluster, have a significantly broader RV distribution. The dashed lines show the simultaneous Gaussian fits to the cluster and field RV distributions. We use these Gaussian fits to calculate membership probabilites for each individual star in the cluster.

Radial-velocity (RV) histogram for stars in the field of M35. Cluster members are clearly identified by the sharp peak in the distribution at the mean RV of about -8 km/s. Stars in the Glactic field, not associated with the cluster, have a significantly broader RV distribution. The dashed lines show the simultaneous Gaussian fits to the cluster and field RV distributions. We use these Gaussian fits to calculate membership probabilites for each individual star in the cluster. Radial-velocity (RV) as a function of orbital phase for the blue straggler binary ID 7782 in NGC 188. This particular binary is "double lined" meaning that we detect the flux from both stars in our spectra. The primary RVs are shown in the solid points, and the secondary RVs are shown in the open circles. The lines show the kinematic orbital solution. In the bottom panel, we show the RV residuals (observed - expected) .

Radial-velocity (RV) as a function of orbital phase for the blue straggler binary ID 7782 in NGC 188. This particular binary is "double lined" meaning that we detect the flux from both stars in our spectra. The primary RVs are shown in the solid points, and the secondary RVs are shown in the open circles. The lines show the kinematic orbital solution. In the bottom panel, we show the RV residuals (observed - expected) .

Visualization showing a snapshot in time from an N-body open cluster simulation. The simulation was created using the nbody6 code, and this image was created using my personal visualization software.

Visualization showing a snapshot in time from an N-body open cluster simulation. The simulation was created using the nbody6 code, and this image was created using my personal visualization software. Comparison of the NGC 188 N-body model to our observations. The left panels compare the observed (black line) and simulated (gray-filled) main sequence period (top) and eccentricity (bottom) distributions. The right panel compares the simulated (left) and observed (right) color-magnitude diagrams (with the main-sequence binaries used for the left panels marked in gray). The initial binaries for the NGC 188 simulation were based directly on our observations of the binary population in the young (150 Myr) open cluster M35. The simulation was constructed using the nbody6 code. The remarkable agreement between the binary population in the model and that of the true cluster in both frequency and distributions of orbital parameters demonstrates the power of using detailed observations to guide sophisticated N-body simulations.

Comparison of the NGC 188 N-body model to our observations. The left panels compare the observed (black line) and simulated (gray-filled) main sequence period (top) and eccentricity (bottom) distributions. The right panel compares the simulated (left) and observed (right) color-magnitude diagrams (with the main-sequence binaries used for the left panels marked in gray). The initial binaries for the NGC 188 simulation were based directly on our observations of the binary population in the young (150 Myr) open cluster M35. The simulation was constructed using the nbody6 code. The remarkable agreement between the binary population in the model and that of the true cluster in both frequency and distributions of orbital parameters demonstrates the power of using detailed observations to guide sophisticated N-body simulations.  Semi-major axes as functions of time for the planets in our Solar System, produced using the Mercury planetary system integrator. The gray lines show the normal unperturbed system, and the black lines show what our Solar System would look like in the 200 years following a weak dynamical encounter with another star, for instance within an open star cluster. Neptune, Uranus and Saturn are ejected from the system. The rest of the planets survive, but their semi-major axes (as well as eccentricities, and inclinations) are modified, with Jupiter's orbit changed most significantly. I will use as similar method to model the dynamical evolution, including the effects of stellar encounters, of planetary systems within star clusters.

Semi-major axes as functions of time for the planets in our Solar System, produced using the Mercury planetary system integrator. The gray lines show the normal unperturbed system, and the black lines show what our Solar System would look like in the 200 years following a weak dynamical encounter with another star, for instance within an open star cluster. Neptune, Uranus and Saturn are ejected from the system. The rest of the planets survive, but their semi-major axes (as well as eccentricities, and inclinations) are modified, with Jupiter's orbit changed most significantly. I will use as similar method to model the dynamical evolution, including the effects of stellar encounters, of planetary systems within star clusters.